The big thing in Physics news lately has been the results from the OPERA experiment which showed that these sub-atomic particles called neutrinos were travelling slightly faster than photons, the massless particles that light is made of, would have. This result is especially interesting because according to Einstein's theory of Relativity, nothing is supposed to be able to travel faster than the speed of light. You can read about these results all over the internet (here and here, for example), but the basic idea is that scientists at CERN shot some very high-energy neutrinos through the Alps and into a detector, which measures how long it took them to get there. What was found was that the neutrinos reached the detector 60 nanoseconds faster than they would have if they were traveling at the speed of light.

It might be useful to talk a bit about what neutrinos actually are. These weakly-interacting, neutral elementary particles were first proposed to exist by Wolfgang Pauli in the 1930s to help conserve energy and momentum in a process called beta decay, but weren't detected until 1956 in an experiment using beta-capture, where an anti-neutrino and proton combine to make a neutron and positron. Nowadays, we routinely detect neutrinos coming from the sun and from distant supernova explosions. This little particle was central to a scientific conundrum called the "Solar Neutrino Problem" where only about a third of the number of neutrinos expected to be coming from the sun were detected. This was solved by the discovery that neutrinos have mass (though a very small one), and come in three different types which they can oscillate between at random.

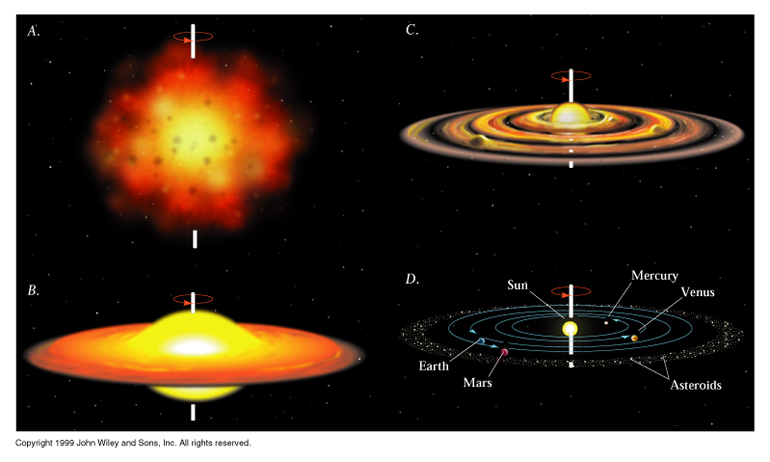

The layout of the OPERA experiment.

Since neutrinos are supposed to have mass, the results from the OPERA experiment are mildly disturbing. Relativity is founded on the principle that objects with mass cannot travel at the speed of light, much less faster than it, and if neutrinos can, in fact, travel faster than the speed of light, then we would have to seriously change all our ideas about spacetime and gravity. Fortunately, this is a very preliminary result, and there is a good chance that it's wrong. Not that the scientists performing the experiment were bad at their job or anything, but there are many sources of error that might pop up. As someone once said, "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence." That means that physicists probably aren't going to take these results seriously until another experiment can verify them.

I'll certainly be keeping an eye on it... already there are a flurry of papers on the arXiv attempting to explain the OPERA results. If you want to read the original paper, check it out here.